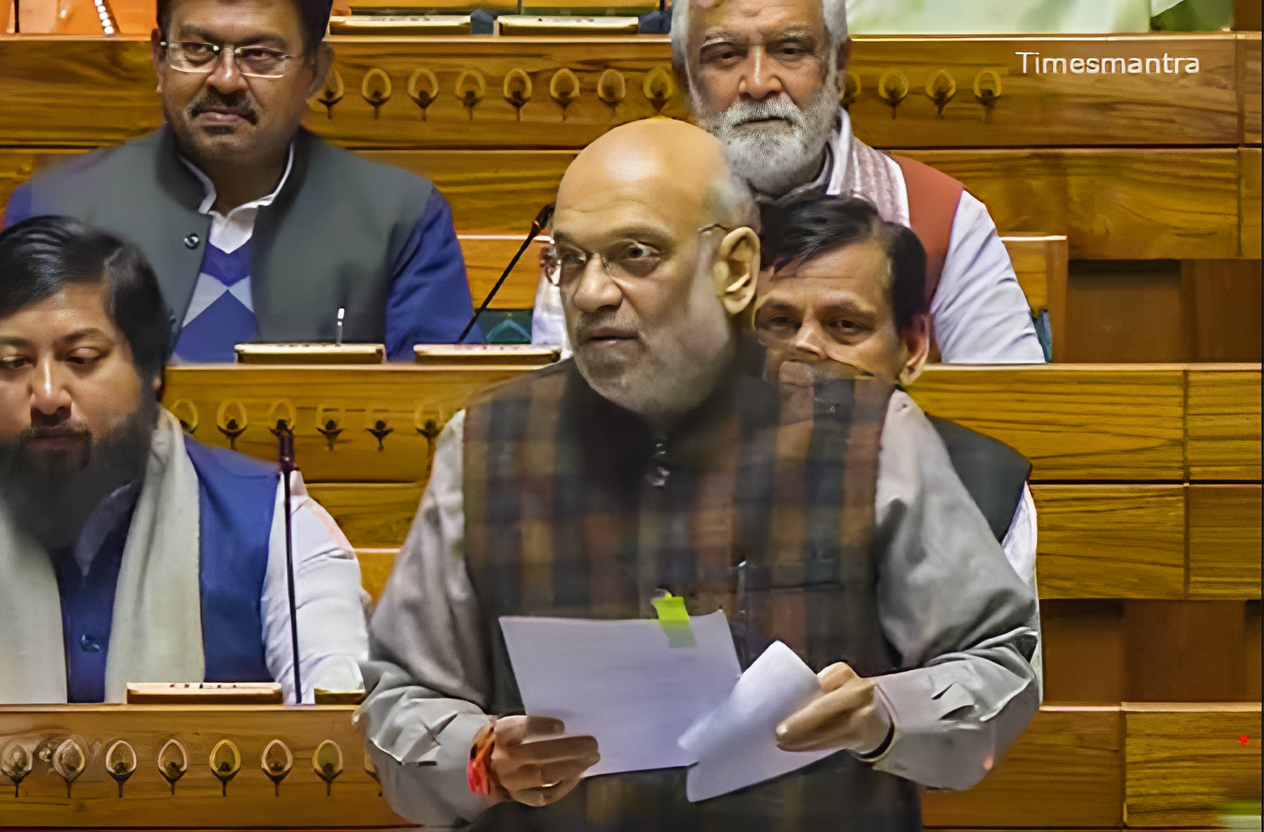

A Landmark Legislative Push: Amit Shah Tables Bills to Remove Leaders in Custody

In a move set to redefine India’s political and legal landscape, Union Home Minister Amit Shah has tabled three landmark bills in the Lok Sabha. These bills propose a new legal framework for the mandatory removal of a sitting Prime Minister, Chief Minister, or minister if they are arrested and detained in custody for a period of 30 consecutive days on serious criminal charges. The introduction of this legislation on August 20, 2025, just days before the end of the Monsoon Session, has ignited a fierce nationwide debate on constitutional morality, governance, and the potential for political misuse.

The Legislative Package: Three Interconnected Bills

The three bills tabled by Amit Shah are a strategic and comprehensive effort to address what the government calls a “legal vacuum” in the existing political framework. The three bills are:

- The Constitution (130th Amendment) Bill, 2025: This is the most significant of the three, as it directly seeks to amend Articles 75 and 164 of the Constitution of India. The core provision is that a Prime Minister, Union Minister, or a Minister in a State Council of Ministers who is arrested and detained in custody for a continuous period of 30 days on charges carrying a punishment of five years or more must tender their resignation on the 31st day. If they fail to do so, they will automatically cease to hold office. The government’s Statement of Objects and Reasons for the bill argues that a minister facing serious criminal allegations and in custody may “thwart or hinder the canons of constitutional morality and principles of good governance” and diminish public trust.

- The Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation (Amendment) Bill, 2025: This bill extends the same principle of accountability to the Chief Minister and ministers in the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir. It proposes to amend Section 54 of the Jammu and Kashmir Reorganisation Act, 2019, to provide a specific legal mechanism for the removal of leaders who are arrested and detained on serious criminal charges for a continuous period of 30 days.

- The Government of Union Territories (Amendment) Bill, 2025: This bill is designed to amend the Government of Union Territories Act, 1963, to bring Puducherry and the National Capital Territory of Delhi under the purview of this new legal framework. The Chief Ministers and ministers in these Union Territories would also be subject to the 30-day custody rule.

The government has also moved a motion to refer all three bills to a Joint Parliamentary Committee (JPC) for further scrutiny, indicating a willingness to engage in a detailed and bipartisan discussion on the matter.

The Rationale: Upholding Public Trust and Governance

The government’s primary argument for this legislation is that it will strengthen public accountability and address the issue of the criminalization of politics. Currently, the law only provides for the disqualification of a Member of Parliament (MP) or a Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA) upon their conviction for a crime. There is no existing provision in the Constitution for the removal of a minister solely based on their arrest or detention, even on serious charges.

This legal gap has been a point of contention for years. While a civil servant is suspended from duty upon being detained for more than 48 hours, a minister, who holds a higher position of public trust, has been able to remain in office even after being in custody for an extended period. The government’s move seeks to close this loophole, arguing that a leader who is in continuous custody cannot effectively perform their duties and that their continued presence in office erodes the constitutional trust placed in them by the people. The bills’ proponents also highlight that the provisions allow for the re-appointment of the minister or chief minister upon their release from custody, should they be acquitted of the charges.

Opposition’s Concerns: A “Draconian” Tool for Political Vendetta

The Opposition has reacted with strong criticism, calling the bills a “draconian” measure that could be used as a political weapon. Leaders from various opposition parties, including the Congress and the Aam Aadmi Party, have expressed concerns that the legislation could be misused by the central government to destabilize state governments run by opposition parties.

The primary fear is that central investigating agencies, such as the Enforcement Directorate (ED) and the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), could be used to arbitrarily arrest and detain political opponents on fabricated charges. If a Chief Minister or a minister from a non-BJP-ruled state is held in custody for 30 days, they would automatically be removed from office, a move that critics argue could be a backdoor way to topple democratically elected governments. This concern is not entirely unfounded, given the recent trend of high-profile arrests of opposition leaders on corruption charges.

Some critics have also pointed out that the bills do not distinguish between an arrest on serious criminal charges and an arrest in a case where the charges are of a less grave nature, as long as the minimum imprisonment is five years or more. This lack of nuance, they argue, makes the legislation vulnerable to misuse.

Political Context and Precedent

The timing of these bills is particularly significant. In recent years, India has seen several high-profile instances where Chief Ministers and ministers have been arrested but refused to resign. Former Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal and Tamil Nadu Minister V. Senthil Balaji are two prominent examples. While the Supreme Court had in some cases nudged leaders towards stepping down, there was no legal obligation to do so. The new bills would change this precedent and give a legal basis for their removal.

The decision to send the bills to a JPC is a strategic move by the government. It allows for a more detailed and bipartisan discussion, which could help in addressing some of the Opposition’s concerns and potentially lead to a more robust and effective piece of legislation. It also prevents the Opposition from a last-minute filibuster in the session and allows the government to demonstrate its willingness to engage with other parties.

Conclusion: A Turning Point in Indian Governance

The introduction of these three bills marks a crucial moment in India’s legislative history. The proposed laws seek to address a fundamental question of political accountability that has long been a topic of debate. The government’s push for this legislation, rooted in the principles of constitutional morality and public trust, has been met with significant resistance from an Opposition that fears it could be a tool for political vendetta.

The debate in Parliament and within the JPC will be critical in shaping the final form of these bills. The outcome will not only redefine the rules of political conduct but also test the strength of India’s democratic institutions. The balance between the presumption of innocence and the demand for ethical governance is at the heart of this discussion, and the final version of these bills will have a lasting impact on the future of Indian politics.