Kerala Confronts a New Public Health Crisis: The Surge in Brain-Eating Amoeba Cases

The state of Kerala, celebrated for its high health indicators and robust public health infrastructure, is facing a grave and unprecedented health emergency. A recent and alarming surge in cases of the deadly “brain-eating amoeba,” Naegleria fowleri, has prompted a state-wide alert and highlighted the vulnerability of even the most advanced healthcare systems to microscopic pathogens. This rare but almost invariably fatal infection, known as Primary Amoebic Meningoencephalitis (PAM), has claimed numerous lives, creating a sense of fear and urgency among health officials and the public.

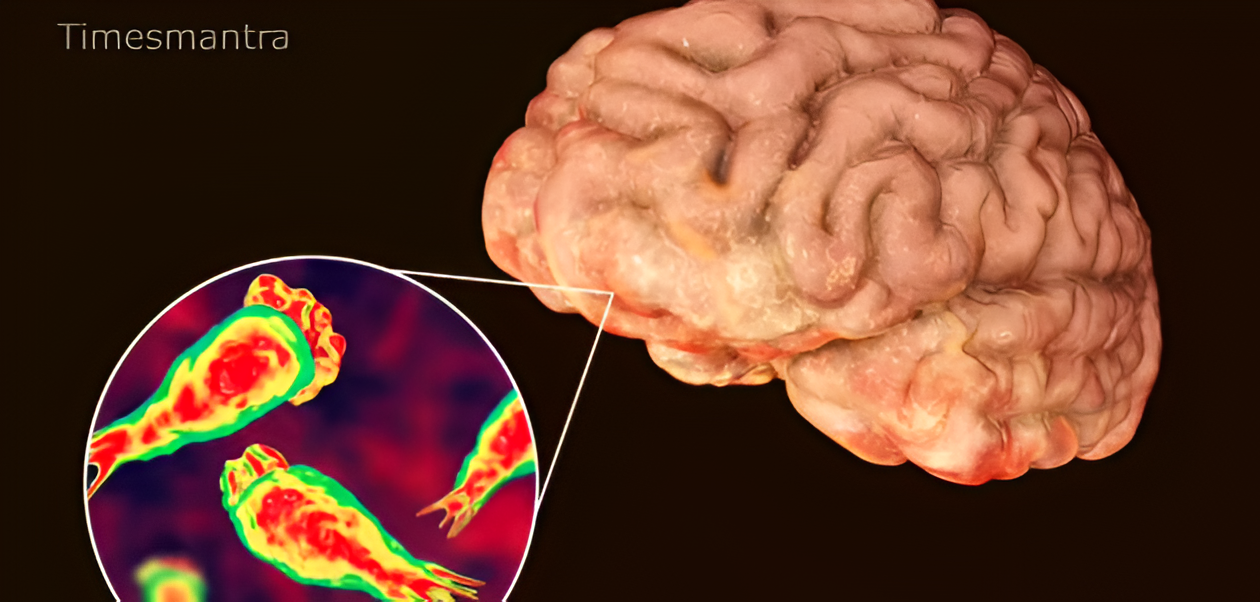

Understanding the Microscopic Killer: Naegleria fowleri

Naegleria fowleri is a free-living amoeba, a single-celled organism found in warm freshwater environments such as lakes, ponds, rivers, and hot springs. It thrives in temperatures ranging from 25°C to 40°C, making it a particular concern in tropical and subtropical regions. The term “brain-eating amoeba” is scientifically descriptive: the amoeba does not infect a person through ingestion. Instead, the infection occurs when contaminated water, typically containing the amoeba in a dormant state, enters the nasal passages forcefully, often during swimming, diving, or nasal cleansing. Once inside the nose, the amoeba travels up the olfactory nerve to the brain, where it causes a severe, rapidly progressing infection that destroys brain tissue.

The resulting disease, PAM, is characterized by a high fever, severe headache, nausea, and vomiting in its early stages. These symptoms can be easily mistaken for more common illnesses like bacterial or viral meningitis, leading to a crucial and often fatal delay in diagnosis. As the infection progresses, neurological symptoms such as confusion, seizures, hallucinations, and loss of balance appear, often leading to a coma and death within a week or two of the onset of symptoms. The global fatality rate for PAM is devastatingly high, exceeding 97% of reported cases.

The Alarming Surge in Kerala

While Naegleria fowleri infections are rare worldwide, Kerala has seen an unprecedented spike in cases since 2024. Historically, India has reported only a handful of cases, with very few documented in Kerala until recent years. A worrying trend began to emerge, culminating in a significant surge. According to reports, Kerala recorded 36 cases and nine deaths in 2024, but even more alarmingly, the number of confirmed cases has risen to 42 in 2025 alone, with five fatalities reported in a single month.

The victims have ranged in age from a three-month-old infant to a 56-year-old woman, underscoring that no age group is immune. The most affected regions have been the northern districts of Kozhikode, Malappuram, and Wayanad, which are abundant in the freshwater bodies where the amoeba thrives. Many of the patients had a history of bathing or swimming in ponds or other untreated water sources, highlighting the direct link between exposure and infection. For instance, a three-month-old from Omassery in Kozhikode was infected from water drawn from a well that tested positive for the amoeba, while a 9-year-old girl in Thamarassery tragically succumbed to the infection after a rapid deterioration of her condition.

This rise in cases has been attributed to a disturbing confluence of factors. Climate change, with its accompanying rise in atmospheric and surface water temperatures, creates a more favorable environment for the amoeba to multiply. Additionally, unchecked contamination of wells and ponds with sewage and organic waste provides a ready food source for the amoeba. Cultural practices, such as ritual nasal cleansing using unsterile water, also provide a direct pathway for the amoeba to enter the body.

A Proactive Public Health Response

In response to the escalating crisis, Kerala’s health department has launched a multi-pronged public health campaign. Officials have invoked the State Public Health Act to intensify preventive measures and public awareness drives. The immediate focus is on educating the public and restricting access to high-risk water bodies.

A key government initiative is the “Water is Life” (Jalamanu Jeevan) campaign. This state-wide drive involves the chlorination of wells and water tanks, as well as the cleaning of public water bodies. Local self-government bodies, in collaboration with the Health and General Education Departments, are at the forefront of this effort. Schools are playing a crucial role by conducting awareness programs to teach children about safe water practices. The message is simple and direct: avoid swimming or bathing in stagnant or untreated freshwater, especially during periods of high temperature, and use only boiled, distilled, or sterile water for nasal cleansing. The state’s response has also involved the procurement of essential medicines, including miltefosine, which has shown promise in the rare cases of survival globally.

The Race Against Time: Diagnosis and Treatment

The high mortality rate of PAM is not only due to its aggressive nature but also to the difficulty of timely diagnosis. The initial symptoms—fever, headache, and neck stiffness—are non-specific and can mimic bacterial meningitis. A definitive diagnosis requires specialized lab tests to identify the amoeba in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The rapid progression of the disease means there is a very narrow window for effective intervention.

Medical preparedness is another critical component of the response. The state has issued detailed treatment protocols for doctors and is ensuring the availability of essential medications. The primary drug for treatment is the antifungal amphotericin B, often administered in combination with other drugs like miltefosine and fluconazole. These treatments are most effective when administered in the very early stages of the disease, making public awareness and swift medical consultation paramount. The success stories, though few, underscore this point. In some of the rare cases of survival, including a 14-year-old boy in Kozhikode who became the first patient in India to survive the infection in 2024, early diagnosis and an aggressive, multi-drug treatment regimen were the decisive factors. The state’s ability to conduct rapid diagnostic tests locally has been a significant advantage, reducing the delay that was common when samples had to be sent to other parts of the country.

A Warning for the Future

The surge of Naegleria fowleri in Kerala serves as a stark warning about the evolving landscape of public health. As global temperatures continue to rise, thermophilic organisms like this amoeba will find more favorable habitats, potentially expanding their geographical reach. The convergence of climate change, environmental contamination, and common human practices creates a perfect storm for the emergence of new or previously rare diseases.

For a state like Kerala, which has set a global standard in healthcare, this outbreak is a profound test. It demonstrates that even with a strong healthcare system, vigilance, public education, and environmental management are non-negotiable in the face of a changing climate and a world of microscopic adversaries. The public health response in Kerala is a model of proactive crisis management, but the ultimate success will depend on sustained efforts to clean water bodies, educate the populace, and remain on high alert for what may be a growing threat. The battle against this “brain-eating amoeba” is a microcosm of a larger global challenge: adapting our health systems and our daily lives to a new and warmer world where unseen dangers are becoming increasingly present