Parasakthi Movie Review: A Timeless Socially Powerful Classic

Seventy-three years after its groundbreaking release, Parasakthi (1952) stands as an unyielding pillar of Tamil cinema, a film that didn’t just entertain but ignited a social revolution. Directed by the acclaimed duo Krishnan-Panju and produced by T.R. Sundaram under Modern Theatres, this black-and-white epic—adapted from P. Kanthan’s eponymous play—launched Sivaji Ganesan into the pantheon of Indian acting legends while delivering a scathing critique of caste hierarchies, religious exploitation, and the plight of widows. Clocking in at 188 minutes, Parasakthi weaves a tragic tapestry of rural oppression, where a young man’s quest for justice exposes the rot beneath societal piety. With its incendiary dialogues like “Deivathin arul illamal evarum jeevikkave mudiyathu” (No one can live without God’s grace), the film courted bans and boycotts upon release, yet grossed ₹1.5 crore—a phenomenal sum then—and ran for 100 days in Madras. Starring debutant Sivaji Ganesan as the vengeful Gunasekaran, Pandari Bai as the resilient widow Valli, R. Nagendra Rao as the tyrannical priest, and S.V. Sahasranamam as the beleaguered father, Parasakthi remains a socially charged classic, influencing Dravidian politics and progressive filmmaking. In 2025, as caste-based atrocities surge (over 50,000 cases per NCRB data), its message thunders louder, proving that true cinema endures by challenging the status quo. This review delves into its narrative fire, stellar portrayals, technical mastery, and lasting legacy—a timeless roar against injustice.

Plot and Themes: A Fiery Indictment of Societal Hypocrisy

Parasakthi unfolds in a sun-baked Tamil Nadu village, where the iron grip of caste and superstition suffocates the innocent. The story orbits the Gunasekaran family: father Parasakthi Iyer (S.V. Sahasranamam), a struggling farmer clinging to orthodox faith; son Gunasekaran (Sivaji Ganesan), a fiery urban returnee radicalized by progressive ideals; and daughter Valli (Pandari Bai), whose widowhood becomes the narrative’s heartbreaking fulcrum. When Valli’s husband dies young, she is thrust into the dehumanizing rituals of widowhood—tonsured head, coarse sari, and ritual isolation—exploited by the lecherous temple priest Natesa Mudaliar (R. Nagendra Rao), who preys on the vulnerable under the guise of piety.

Gunasekaran’s homecoming ignites the powder keg: witnessing his sister’s degradation, he unleashes a torrent of rage against the priest’s temple racket, where “donations” fund debauchery while devotees starve. The plot crescendos in a courtroom showdown, where Gunasekaran indicts not just the man but the system, demanding accountability from divine proxies. Krishnan-Panju masterfully adapt Kanthan’s 1948 play, expanding its stage confines into a panoramic canvas of rural despair, with symbolic motifs—the temple’s looming gopuram as oppressive authority, flickering oil lamps as fleeting hope—amplifying the melodrama.

Thematically, Parasakthi is a Molotov cocktail hurled at Brahminical dominance, echoing Periyar E.V. Ramasamy’s self-respect movement. It skewers superstition’s stranglehold, portraying rituals as tools of control rather than salvation, and champions widow remarriage—a radical stance in 1950s India, where such unions were taboo. Caste’s insidious web binds the narrative: the Iyer family’s “upper” status crumbles under priestly machinations, blurring hierarchies to reveal universal exploitation. Anti-clerical fury peaks in Gunasekaran’s tirade—”The god you worship is the devil you fear”—a line that fueled 1952 bans by the Congress government. Yet, its humanism transcends: redemption arcs for minor characters underscore reform’s possibility. In an age of algorithmic echo chambers, Parasakthi‘s unfiltered fury feels revolutionary, a blueprint for films like Jai Bhim that dare to disturb.

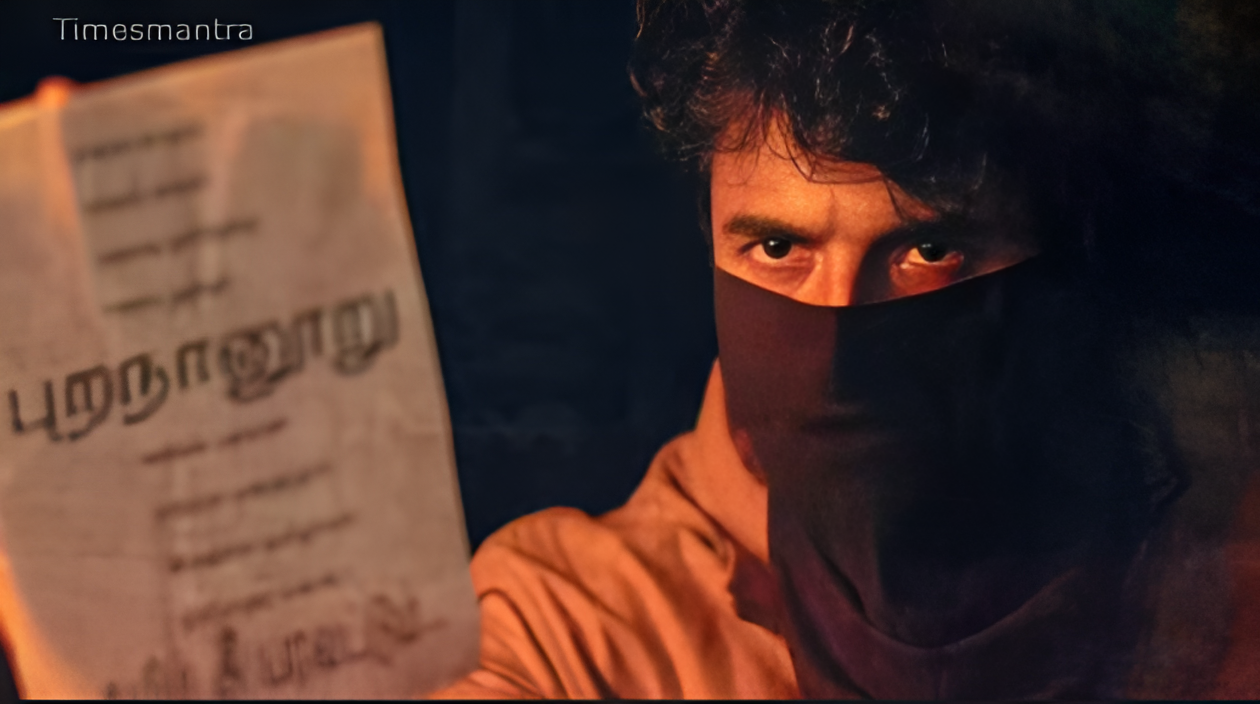

Performances: Sivaji Ganesan’s Explosive Debut

Parasakthi‘s soul ignites through its performances, with Sivaji Ganesan’s debut as Gunasekaran a supernova that redefined acting in Indian cinema. At 27, the theater-honed thespian channels volcanic intensity—eyes flashing with righteous fury, voice modulating from whispered anguish to thunderous oratory. His courtroom soliloquy, a 12-minute tour de force dissecting faith’s facade, earned standing ovations at previews and cemented his “Nadigar Thilagam” (Supreme Actor) moniker. Ganesan’s physical transformation—from slouched defeat to defiant poise—mirrors Gunasekaran’s arc, drawing from his New Theatres stage roots for nuanced emotional layering.

R. Nagendra Rao’s Natesa Mudaliar is villainy incarnate: a slimy fusion of sanctimony and sleaze, his oily baritone and predatory smirks evoking real-life temple tyrants. Rao’s subtlety— a fleeting remorse in private moments—adds depth, making the priest pitiable yet unforgivable. Pandari Bai’s Valli is a quiet storm: her widow’s restraint—stifled sobs, averted gazes—conveys profound suffering, her silent rebellion a feminist precursor in male-dominated narratives. S.V. Sahasranamam’s Parasakthi Iyer embodies tragic faith, his crinkled face a map of conflicted piety, while K.A. Thangavelu’s comic interludes as the hapless servant provide cathartic levity.

The ensemble’s synergy, under Krishnan-Panju’s precise direction, elevates Parasakthi beyond melodrama. Ganesan’s chemistry with Bai—brotherly protectiveness laced with shared pain—anchors the emotional core, influencing mentor-apprentice dynamics in later Ganesan vehicles like Veerapandiya Kattabomman. In 2025’s era of method acting, their raw immersion—rehearsed in actual villages—sets a gold standard, proving authenticity trumps artifice.

Technical Mastery: Black-and-White Brilliance

For a 1952 venture, Parasakthi‘s technical finesse astonishes, its black-and-white palette a deliberate canvas for moral shadows. Cinematographer S. Maruthi Rao’s chiaroscuro lighting—harsh sun bleaching village squalor, deep umbras cloaking temple intrigue—evokes Eisenstein’s montage, with fluid dolly shots during confrontations heightening tension. The 1.33:1 aspect ratio confines action to intimate frames, amplifying claustrophobia in widow’s quarters and courtroom cages.

Editor K. Shankar’s rhythmic cuts build inexorably, interspersing lyrical village idylls with ritualistic horror for visceral impact. R. Sudarsanam’s score, with haunting flute leitmotifs and choral swells, underscores pathos—the title track “Deivathin Arul” a devotional dirge that became a cultural staple. Lyrics by Kothamangalam Subbu and Vali pack philosophical punches, like “Kaalam varum varai kaathiruppathu” (Waiting for time to change), blending bhakti with bite.

Sound design, rudimentary yet evocative, relies on diegetic echoes—temple bells tolling like judgments, wind whispering through palm fronds. The 2015 digital remaster, screened at IFFI Goa, preserves its grainy authenticity, with 4K upscaling revealing forgotten details like sweat beads on Ganesan’s brow. Krishnan-Panju’s craftsmanship—drawing from Neorealism—transforms constraints into strengths, making Parasakthi a technical triumph that ages like aged arrack: sharp, smooth, soul-stirring.

Social Impact: Revolution in Reels

Parasakthi‘s release was a socio-political bombshell. Banned by the Brahmin-led Congress regime for “inciting communal hatred,” it fueled DMK protests, with M. Karunanidhi screening pirated prints in clandestine halls. The 1953 lift, post-Congress’s poll rout, symbolized Dravidian ascent, grossing ₹1.5 crore and running 133 days in Chennai.

Its ripples reshaped society: influencing the 1956 Hindu Marriage Act’s remarriage provisions and Periyar’s anti-caste crusades. Ganesan’s stardom empowered Dalit audiences, inspiring actors like N.T. Rama Rao. Globally, it screened at 1953’s Venice Film Festival, earning plaudits for “raw realism.” In 2025, amid #CasteCensus demands, its dialogues fuel Twitter storms, remixed in reels against temple land grabs.

Critics flag dated elements—melodramatic flourishes—but its boldness endures, a progenitor of socially conscious cinema like Kaala.

Enduring Relevance: Echoes in Contemporary Chaos

In 2025’s fractured landscape—caste violence up 15% (NCRB)—Parasakthi mirrors modern maladies: widow suicides (800 annually) and priestly scandals evoke its pleas. Ganesan’s monologues inspire activists, while restored prints at MAMI Mumbai affirm archival urgency.

Yet, it provokes: the film’s Brahmin-bashing risks caricature, a critique from scholars like A.K. Ramanujan. Still, its empathy—reform over revenge—transcends, urging viewers to dismantle dogmas in an age of deepfakes and divine influencers.

Conclusion

Parasakthi is no dusty relic—it’s a raging inferno, its 1952 flames fanned by Sivaji Ganesan’s inferno, Krishnan-Panju’s vision, and Kanthan’s quill. A socially powerful classic that shattered silences, it demands rewatches for its defiant heart. Rating: 9.5/10—eternal, explosive, essential. In cinema’s vast vault, it burns brightest, a beacon for the bold.